Neither the COVID-19 pandemic nor the 1918 influenza pandemic were the only public health crises to have taken massive tolls on the United States during the last century. In the 1940s, polio outbreaks were commonplace and highly feared. After many years, a successful vaccination effort almost entirely eradicated polio (with the exception of Pakistan and Afghanistan, where polio is endemic). Many hoped that we could learn from the history of the polio vaccination effort to guide us through the COVID-19 crisis. However, a concerning trend is unfolding. Rather than our polio history guiding us to better outcomes amidst the COVID pandemic, vaccine skepticism brought on by the pandemic is leading to the re-emergence of polio. In July of 2022, an unvaccinated man in New York contracted polio and has begun to experience paralysis as a result of contracting the virus. This was the first case of polio in New York in 10 years.

Wastewater data in NYC suggests that this infection is the tip of the iceberg, and that one symptomatic case suggests hundreds more. Rising levels of unvaccinated populations are causing scientists to sound alarms, warning that declining vaccination rates will lead to the return of other once-contained diseases, greater levels of sickness and death among children and adults, and significant strain on our healthcare systems.

History tends to repeat itself, and certainly in 2020, when the rapid effort to develop a COVID-19 vaccine raised suspicion amongst many in the general population, scientists and historians recalled both the effort to develop a polio vaccine and the work of convincing the public to take it. Now history is repeating itself in a far more literal way, as polio re-emerges at a time when vaccine skepticism is high. We’re looking to the history of the polio vaccine, and how it informs our efforts to vaccinate against COVID-19, polio, and other viruses.

Polio’s Dark History Led to Scientific Breakthroughs

Poliovirus and the novel coronavirus are both viruses, of course, but there are some interesting similarities in the ways society has dealt with — and now continues to deal with — both of them. In comparing the two viruses, it’s important to start with the history of polio.

In the 1940s, poliomyelitis had been appearing seasonally, typically during the late summer months– eventually deemed “polio season.” Across the United States, and seemingly without warning, children were becoming paralyzed after contracting the disease. Cities and towns alike came to a standstill, with public officials shutting down public pools, closing theaters, and bringing education and summer programs to a halt. Little was known about the virus, only that it mysteriously flared during the warmest days of the year. Everyone was told to avoid drains and unscreened windows, to go out in public as little as possible, and to avoid crowds. The panic was so widespread that insurance companies even started selling polio insurance to parents of newborns.

Descriptions of the threatening conditions surrounding polio sound as if they’d fit into a dystopian film world: “Health workers in New York City would physically remove children from their homes or playgrounds if they suspected they might be infected. Kids, who seemed to be targeted by the disease, were taken from their families and isolated in sanitariums.”

Whereas COVID-19 has become a disease affecting people of all ages, polio primarily affected young children. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was a very public example of an adult who experienced polio’s hallmark paralysis later in life, but infections in children were much more common. Entire hospital wards were set up with iron lungs — large, tank-sized ventilators that stimulated breathing using negative pressure — to counteract polio’s lung-paralyzing effects.

Developing the Polio Vaccine

From an annual peak of 21,000 cases of polio-induced paralysis in 1952 in the U.S., the introduction of the polio vaccine in 1955 resulted in a steady decline in cases. The U.S. then successfully eradicated polio in 1979. By 2019, the World Health Organization reported fewer than 100 cases of polio around the world. How did this happen?

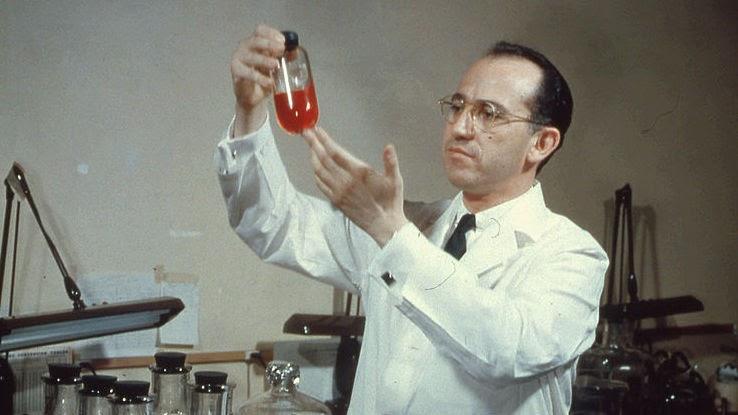

Jonas Salk and his team engaged in a campaign for vaccine research and deployment that we can learn from today. In the 1950s, there was no government-funded initiative for vaccine development, such as the Operation Warp Speed that was established during the COVID pandemic. Developing a response to poliovirus fell largely on the private sector, spurred by a new entity called the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which was founded by Roosevelt in 1938.

Salk had begun developing the polio vaccine in 1948 after receiving a grant to study the virus at the University of Pittsburgh. The physician set to work on an inactivated vaccine — one that used dead strains of poliovirus to create immunity once injected. After formulating a promising vaccine candidate in 1950, he then began testing it on himself, his family members, and former polio patients. In 1953, Salk revealed his findings on a CBS national radio program.

Salk’s announcement led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for clinical trials of the vaccine. Throughout 1954, the new polio vaccine was tested on over 1.6 million children aged 6 to 9, who became known as “Polio Pioneers.” It was the largest medical study ever conducted at the time. The results of the clinical trial were announced in April 1955. The vaccine was up to 90% effective in preventing paralytic polio infection. But this good news only lasted so long.

It Wasn’t All Successful

Immediately following the clinical trials results announcement in 1955, the government licensed several companies to start producing vaccines. This was accomplished within hours of the announcement. Speed was a primary focus, just as it has been during the race to develop the COVID-19 vaccines. The very next day, a campaign for the production of the polio vaccine had begun.

But within just a few days, there were reports of children who developed polio and even paralysis after getting the vaccine. This was due to an incorrect lab process used by some manufacturers, which resulted in some vaccines containing live virus. Despite this, vaccinations continued for weeks due to minimal federal oversight and political pressure. The U.S. Surgeon General did halt vaccinations, but ultimately over 120,000 people received the faulty vaccines containing live poliovirus. The government implemented new processes for reviewing the lab processes and testing all new vaccine shipments, which resolved the problem, and then production was re-started.

Subsequent years saw the development of another polio vaccine, by Albert Sabin. His vaccine uses a weakened version of the live virus and is given by mouth instead of an injection. Because the Salk vaccine was already approved in the U.S. it was difficult to create interest in clinical trials for a new vaccine. Sabin therefore conducted his clinical trials in Africa, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia, where he tested the vaccine on over 100,000 children. The World Health Organization (WHO) then verified the clinical trial results. This was important because of the political tensions and international distrust during this time, due to the Cold War. After it was verified, the Sabin vaccine was quickly found to be a great tool for mass vaccinations because it is given as oral droplets.

Today, millions of people have been safely vaccinated against polio. Vaccine-induced polio is extremely rare and both polio vaccines are considered very safe. In the United States, only the inactivated polio vaccine (the original Salk vaccine) is approved for use by the FDA. Today, these vaccines carry zero risk of causing vaccine-induced polio. In other parts of the world, the oral polio vaccine (the Sabin vaccine) is administered. These use an extremely weakened version of the virus, and in very rare cases, can cause actual polio infection. Though there are good reasons to use the oral polio vaccine (the sort of immunity they confer not only protects individuals but also halts spread), news of vaccine-induced polio may very well contribute to increased vaccine-hesitancy.

Vaccines are Safer Than Ever, Yet Vaccine Hesitancy is on The Rise

The story of Salk’s polio vaccine served as a “cautionary tale” for developers working to ensure the safety of polio vaccines, and more recently, the safety of COVID-19 vaccines. It led to the development of stricter policies and better surveillance tools, to ensure that such a production error cannot go unnoticed again. Thankfully, there have been no reported cases of vaccine-induced COVID-19. This is partially due to the fact that the COVID-19 vaccine development process was very carefully conducted. In fact, it wasn’t nearly as rushed as it appeared from the outside. COVID-19 is a new member of a familiar family of viruses, and a vaccine to target this family of viruses had been in the works for a decade. Still, this hasn’t stopped people from being wary of the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, and this vaccine-hesitancy is becoming more generalized.

The WHO recently reported that 2021 saw the “largest sustained decline in childhood vaccinations in approximately 30 years.” This decline isn’t only due to skepticism. The COVID pandemic has strained healthcare systems and diverted resources. Nevertheless, misinformation about vaccines has become widespread and is a contributing factor to the overall decline in vaccination rates. Vaccination rates against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (the DTP vaccine) are down, alongside vaccinations against HPV. The WHO notes that the cost of this “will be measured in lives.”

Overcoming Mistrust in Vaccines Involves Massive Public Campaigns

What the history of polio can teach us is that we do have the capacity to overcome vaccine mistrust. Getting the vaccination rates for up for standard vaccinations, annual flus, COVID-19, and now monkeypox in the face of rampant political division and public disharmony will take intentional efforts to combat distrust. Options to do so include the following:

- Government officials could initiate public campaigns focused less on trying to correct vaccine-related mythology and more on the actual risks of illnesses.

- Once campaign plans were in place, the next step would involve empowering the right person to deliver that message. One example of a trusted messenger in the United States today is Dr. Anthony Fauci — Americans are more than twice as likely to trust him than distrust him, according to analytics firm YouGov. Voices of non-partisan public health professionals like Dr. Fauci should be amplified.

- On a more local level, trusted family doctors should be equipped and empowered to explain the benefits of vaccination, to encourage inoculation and to provide public health information within their local communities. (There’s no denying that, at a time when resources are stretched thin, asking family physicians to do more is asking quite a bit.)

- We must accept that government spokespersons are not necessarily trusted voices and expect local public health officials to partner with trusted non-government entities, such as churches, schools, community groups, businesses — and, yes, even celebrities and influencers unique to specific communities — to promote vaccinations.

- The US and other resource rich countries must contribute meaningfully to vaccination efforts across the globe, as viruses do not care about borders.

With intentional and persistent investments in science, communication, and trust-building the current vaccination backslide that we’re experiencing can be corrected. You should continue to consult your doctor and the CDC regarding which vaccines you should receive. If you have questions or concerns about the safety of these vaccines, speak with your doctor directly to get answers and information. If you’re a parent, you should also continue to follow up with your pediatrician for all of your child’s vaccination visits. This is the best way to protect them from preventable illnesses.