The greatest works of art — and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 masterpiece, The Godfather, is absolutely one of them — carry down through subsequent generations a kind of inevitability. They contain such perfection that it feels difficult to imagine that they even went through the rigors of being made. I think about this sometimes when I hear, say, “In My Life,” by The Beatles. To me, it’s such a shimmering piece of perfection that it feels nearly untouchable. There’s no lingering messiness to it. It holds its own all the way out into the unimagined future. The Godfather feels like this to me.

Of course, this kind of perfection is one of the happiest illusions art gives us. In reality, The Godfather was anything but inevitable. The tale has been told so often as to feel apocryphal: How Paramount was in the middle of a run of big-budget flops and was wary of suffering another; how an enormous list of great directors turned the project down; how Coppola spent most of the production believing he might be fired at any moment.

Making a movie is infuriatingly collaborative, and on large productions of best-selling source material, there are often too many cooks in the kitchen. Somehow, The Godfather came out the other side with a singular vision; it’s a gigantic, sweeping family story that somehow feels intimate and controlled at all times. It’s a miracle of a movie.

Lots of great movies come and go, though. Besides being an all-time great movie, what’s made The Godfather such a relevant cultural force for five decades? With the digitally remastered 50th Anniversary edition of the movie, which starts streaming on March 22, this is a good opportunity to look at some of the reasons The Godfather has endured and changed the world of movies — and the culture — around it.

The Godfather Invites You In

I’ve always been struck by the fact that The Godfather opens not with Marlon Brando or Al Pacino but with Salvatore Corsitto (playing the thoughtfully-named Amerigo Bonasera) delivering a monologue that begins: “I believe in America.” Coppola doesn’t even show us Brando’s iconic Don Corleone for a full two minutes. Instead, we stay on Bonasera, the undertaker, who asks the Don to murder the men who assaulted his daughter.

This scene is The Godfather-in-miniature, and speaks to its ongoing power. Within one scene, we get a thoughtful articulation of the American dream — and a brutal undermining of that same dream. We enter the movie in this intimate moment with Bonasera because he is us; we want to believe in the promise of America, but when that promise fails, we might be left wanting vengeance. Don Corleone gives a passionate speech about friendship, but when Bonasera leaves the room, we see it’s all just rhetoric. It is both mesmerizing and terrifying. The Godfather is a dark fantasy of absolute power, and right away we see that ultimately this fantasy will betray us.

“The Godfather Effect”

Still, for all its darkness, The Godfather is an iconic story about family and culture, powerfully told. The film undeniably changed American culture in all kinds of ways, but most significantly for Italian Americans. Tom Santopietro’s 2012 book, The Godfather Effect: Changing Hollywood, America, and Me is part film history and part autobiography; in it, Santopietro writes about how the movie, in his words, “helped Italianize American culture.”

The way this happens is obvious in some ways. Gangster movies have always had a kind of coolness about them, and famous, quotable lines like, “Leave the gun, take the cannoli” have become an inextricable part of our lexicon. In other ways though, it’s more subtle. The Godfather, as Santopietro explicates in his book, changed the way Italian Americans thought about their own cultural experience in America.

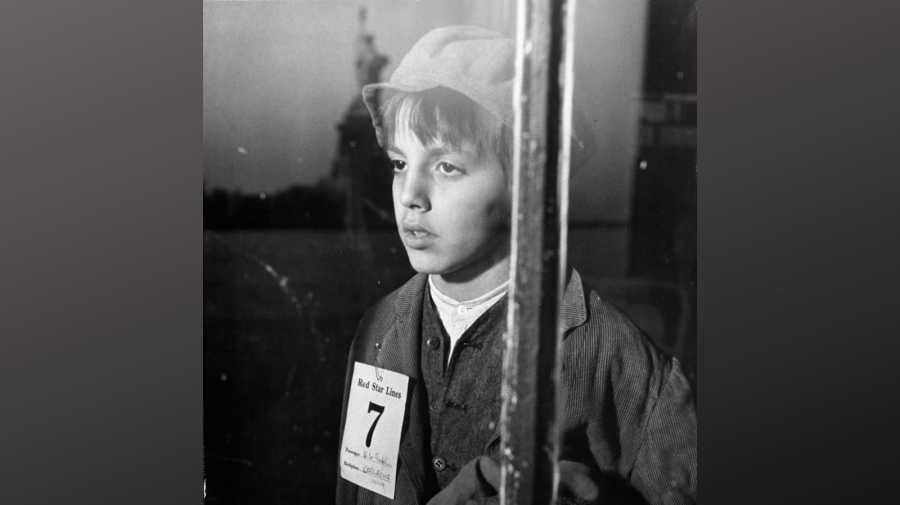

For example, Santopietro points to a moment in The Godfather: Part II (1974) where a young Vito Corleone, on a ship bound for New York City, passes by The Statue of Liberty. In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine in 2012 (also quoted above), Santopietro said this moment of the movie changed him “because when I saw what I felt was my grandfather on that ship coming to America, it was as if I was fully embracing my Italian-ness. I had never really felt Italian until then.” This is the magic of movies: at their best, they can be so indelible that the images in them can help us understand ourselves. The Godfather has been doing that for 50 years now.

The Legacy of the Gangster Film and Beyond

Though Hollywood’s rich history of gangster films began in the 1930s, with films like Howard Hawks’ Scarface (1932) and William Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931), the enforcement of the Hays Code in Hollywood required, among other things, that “Criminals should not be made to be heroes.” The Hays Code was confining in all kinds of ways, but for gangster movies, this meant that — until the Hays Code was abolished in 1968 — crimes had to be punished. After a promising beginning, the gangster movie went into a fallow period.

Arthur Penn’s 1967 crime film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in the title roles, received eight Academy Award nominations, but it really wasn’t until The Godfather that the gangster film came back in full force. The Godfather showed that a gangster film could be a work of art — a story about family, crime, and the myth of the American Dream itself. It’s cool, fun and funny; it’s also epic, dramatic and heartbreaking. It’s beautifully shot and beautifully composed.

And because it’s all these things, its influence has always been overwhelming. Some of the best films of the past 50 years have been gangster films: Martin Scorcese’s Goodfellas (1990), John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991), Joel and Ethan Coen’s Miller’s Crossing (1990). Beyond these examples, The Godfather sends tendrils of influence out into all kinds of movies and TV shows to this day. You see a character sitting ominously behind a desk, and you can’t help but think about Brando as Don Corleone. You get the feeling something ominous is about to happen, and you find yourself thinking about James Caan’s Sonny pulling up to the tollbooth on the turnpike.

The iconic status of The Godfather in our culture makes it an endlessly useful kind of cultural grammar. Its references are so common and so embedded in our culture that they’re able to be understood by people who haven’t even seen the movie yet. I guess that’s the most powerful kind of legacy a film can have: to be an innate part of who we are and how we try to understand ourselves.

As we shift and change, we find that The Godfather remains relevant, which is why this remastered version is so exciting. I mentioned earlier that the film begins with the line, “I believe in America.” It might be the case that what remains so essential about this movie is that we are still learning what that line means about us.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman