Where do you live? Seems like a simple question for most Americans, right? In many ways, it is: you live in a town, and that town is in a state, and that state is part of the United States. That’s all true, and when U.S. citizens think about their identity, these are often the first designations that come to mind.

When it comes to the voting power of citizens in a federal republic, however, things get a little more complicated. Where a citizen votes comes down to which congressional and state district they live in. Because of this, the question of what makes up a district, both on the state and the national level, is incredibly important.

Redistricting, in its simplest form, is just the process of adjusting and readjusting districts based on changes in the area’s population. In reality, it’s far more complicated than that, which is why it ends up being the subject of heated debate in the U.S. time and again. With that in mind, let’s look at some of what you should know about federal redistricting and the problematic version of it known as gerrymandering.

When Does Federal Redistricting Happen?

It’s obvious that in a country as gigantic as the U.S., populations in local areas are constantly changing based on endless factors. People move for as many reasons as there are people. So the question of when the folks in charge decide to count folks living in a given area is important.

Every 10 years, the U.S. government does a full, nationwide census. Because of this, it’s true that rapid population growth might not always show up right away in federal representation. Different states have different rules about when, exactly, they finish their redistricting process, but it always happens in the year or two following the release of the information from the previous census.

What Is Involved in Federal Redistricting?

Once the census is done, it becomes clear how changes in population will begin to impact representation in the federal government. The U.S. Congress is made up of two bodies, the Senate and the House of Representatives. These two bodies work in very different ways in terms of how states are represented within them.

Representation in the Senate is extremely simple: every state gets two seats. Districts don’t matter at all in this context because these elections are statewide. State population doesn’t matter in this context either because every state gets to have two senators no matter its size.

It’s in the House of Representatives that the weight of the population becomes important. Each state automatically gets one representative in the House. There are 435 seats in the House, so the remaining 385 — after accounting for at least one from every state — are determined by population. It’s impossible to get the numbers to divide perfectly, so, as you can imagine, there has been a long history of arguments about how to do the math.

In the end though, it’s pretty much a simple equation where more people means more seats in the House. The amount of seats in the House is the number of congressional districts a given state must create on its map. Many states either gained or lost House seats based on the data from the 2020 census, which is always the case.

How Do States Create Congressional Districts?

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that there are pretty much as many methods for drawing congressional district maps as there are states to draw them. However, there are some common methods and similarities across states that are useful to know.

The main federal requirement for creating districts has to do with equal population. States are required, in drawing federal districts, to make sure each district has roughly the same population. This means some districts have much bigger land area than others. A quick look at New York’s congressional map (below) makes it clear that this can be true to some pretty extreme degrees.

There are, however, some pretty common guidelines that most states tend to follow in drawing their maps. A district should have contiguity, meaning all the parts of the district should be connected. Districts should be based on political boundaries, like town and county lines. As much as possible, districts should also be compact, with the hope that all citizens of a district live close together.

Many states also stipulate that redistricting be done based on “Communities of Interest.” This means that grouping should consider whether voters in a district might have similar voting interests, socioeconomic realities or other factors.

As you can imagine, the feasibility of following all of these guidelines at the same time is often possible, but not always. And that’s why there’s so much room for debate and argument when it comes time to redraw congressional districts in many states.

Okay, So What’s Gerrymandering?

Hopefully you’ve seen by now that the process of redistricting is an absolutely essential one in a representative democracy. On the other hand, the fact that it’s essential means that the stakes are very high. As such, the major political parties have, throughout the history of the U.S. government, attempted to redraw maps to gain advantages in the hunt for additional congressional seats and representation.

The term “Gerrymandering” originated as a portmanteau of Elbridge Gerry, the Governor of Massachusetts in 1812, and a salamander. This was because Gerry’s Jeffersonian Republican party was being accused of manipulating the state’s congressional map in Essex County to the point that one of the districts was shaped like a salamander of some kind.

In general, attempts at gerrymandering involve one of two methods. The first is “cracking,” which is when a group of similar voters are split up across multiple districts to lessen their weight as a voting block. “Packing” is the opposite, and designates when voters are corralled into one district so their power as a voting block doesn’t extend into other districts.

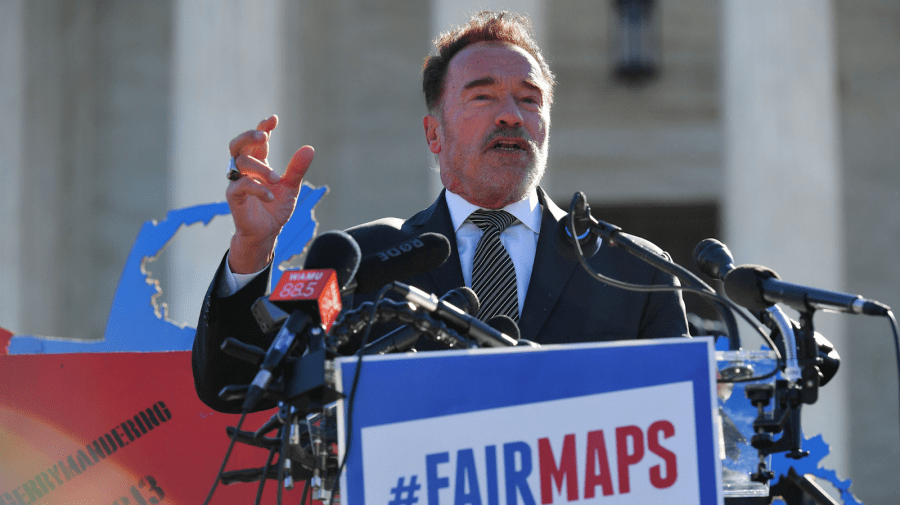

It’s not hard to see why gerrymandering is a problem in a functioning democracy. When legislatures bend the rules to draw more favorable lines, they can manipulate the system into disenfranchising certain voters. Throughout the country’s history, lawmakers have used whatever data they could to bend the redistricting lines in their party’s favor. In many cases, these attempts have been racist as well, and even play into other systemic issues.

What’s more, in 2019 the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in the case of Rucho v. Common Cause that gerrymandering claims by political parties are beyond the scope of the federal courts. That would seem to mean that lawmakers will feel more emboldened than ever to attempt gerrymandering to benefit their political parties.

As the U.S. moves into its next election cycle, folks will start talking about redistricting and gerrymandering again. The recent Supreme Court ruling means that the landscape is about to shift, yet again, in ways that we can’t predict quite yet. The rules of redistricting are meant to protect democracy, but the thing about rules is that, as time goes by, folks tend to come up with ways of getting around them.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman