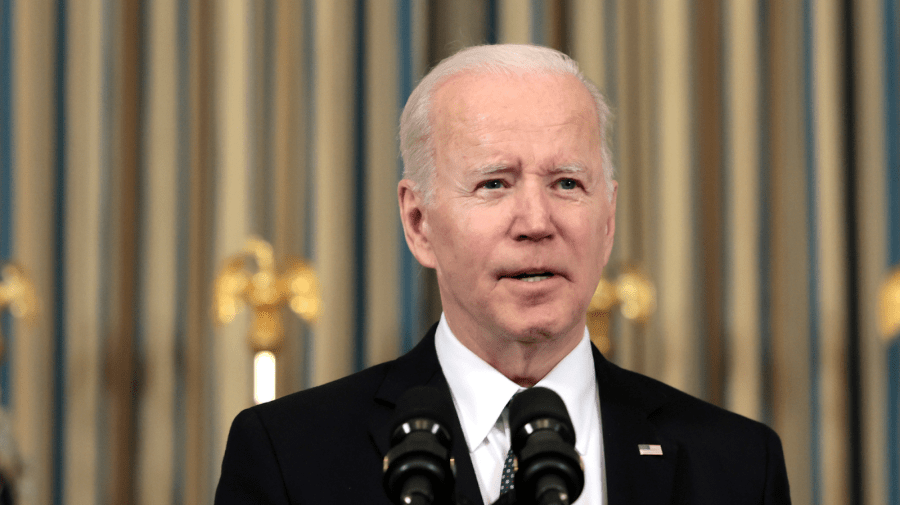

President Joe Biden issued the first pardons of his term on April 26, pardoning three individuals and commuting the sentences of 75 people who — according to a statement from the White House — “are serving long sentences for non-violent drug offenses” and “many of whom would have received a lower sentence if they were charged with the same offense today, thanks to the bipartisan First Step Act.”

The First Step Act, passed in 2018 under the Donald Trump administration, was an attempt to reduce the size of the federal prison population by shortening sentences and providing more ways of avoiding mandatory minimum sentences. The Act has had some positive impacts so far in the short term: the prison population is declining. On the other hand, the implementation of the Act still has a long way to go in terms of implementing programs in prisons designed to help prepare people for life after incarceration.

As the laws on the books shift regarding sentencing for non-violent drug offenses, Biden’s recent pardons are also a shift in the direction of making sure punishments are consistent for people who’re already incarcerated. Whether the administration is going far enough in this direction, however, is a subject ripe for debate.

We Have a Long Way to Go When It Comes to Commuting Sentences

Without question, there is symbolic value in commuting the sentences of 75 people with non-violent drug offenses, but in the immediate aftermath of Biden’s announcement, it’s already clear that this number simply isn’t high enough. The numbers are kind of astonishing: according to the Department of Justice, there are still 18,000 petitions for clemency still pending.

Beyond that, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, roughly 400,000 people are currently incarcerated in the U.S. on drug offenses; while not all of those are non-violent offenders, many of them are. These numbers feel daunting in the face of the small number of sentences commuted. It’s clear that individual cases dealt with piecemeal through the process of petitioning for clemency is not enough. Systemic change is needed to make sure sentences are being commuted fairly and efficiently.

In this light, Biden’s statement that his administration “will continue to review clemency petitions and deliver reforms that advance equity and justice, provide second chances, and enhance the wellbeing and safety of all Americans” feels like little more than lip service given how many people are still locked up, waiting for their “second chances” to come around.

Making Good on Campaign Promises

Of the 75 people Biden granted clemency to, nine had federal charges relating to marijuana specifically. Given that one of Biden’s campaign promises was to decriminalize marijuana, this seems to be an area where the administration is falling woefully short. In spite of the fact that most Americans support this policy, the administration’s movement on it has stalled.

Again, while it’s a step in the right direction that some non-violent, marijuana-related offenders are being given clemency, the small number also serves to highlight the 2,700 people who are still incarcerated on these same charges. The decriminalization of marijuana is an incredibly popular policy in a country that is profoundly divided about almost every issue. According to the Pew Research Center, 60% of Americans believe marijuana should be legal for both medical and recreational purposes, and only 8% believe it shouldn’t be legal at all.

With marijuana already legal in 18 states, it’s clear which way this is trending, culturally. What’s troubling is that as the trend toward federal legalization continues, the people profiting from that shift are almost never the people who were most hurt by the former laws. Broader application of clemency for non-violent drug offenders — especially marijuana-related offenders — would go a long way toward at least beginning to right this long-standing wrong.

Do Americans Really Believe in Second Chances?

The statement from the Biden White House, again, is all about “second chances.” It lays out, specifically, an emphasis on: “greater opportunities to serve in federal government; expanded access to capital for people with convictions trying to start a small business; improved reentry services for veterans; and more support for health care, housing, and educational opportunities.”

Nevertheless, for all the rhetoric about second chances, the United States remains the nation with the highest prison population and the highest incarceration rate in the world. If you can judge a society’s values by its actions, it would seem that the U.S. values the idea of punishment over the idea of second chances.

The evidence, however, suggests again and again that prisons don’t make us safer, and actually lead to the allocation of resources in ways that might end up making us less safe. Prisons don’t even work at keeping people from abusing drugs. Additionally, programs involving drug treatment in lieu of incarceration have been proven to be successful where they’ve been given a chance.

Maybe it’s time to reevaluate the link between crime and punishment in the first place, especially where drug-related, non-violent crime is concerned. The Biden administration’s first acts of clemency are certainly a step in the right direction, but more sweeping changes are needed sooner rather than later.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman