Filling out an NCAA Tournament Bracket is a common ritual every March for everyone from die-hard college basketball fans to people who have never even watched an entire basketball game in their lives. I myself have a long history with these brackets. I’ve got fond memories of getting in trouble with my parents for starting an NCAA Tournament betting pool among my fifth grade classmates back in the ‘90s. Later, when I was in high school, a beloved English teacher gave a gift certificate to a nearby bookstore to the student who had the most correct bracket. Without fail, every year the winner was always someone who didn’t care at all about college hoops.

And this, I think, is part of the enduring appeal of the bracket as a broader notion. It’s an incredibly satisfying concept: you start out with a round number of entries, and one matchup at a time you whittle that number down to one winner. Is that winner unequivocally “the best”? No! That’s the beauty of it. The bracket provides opportunities for irrational hope: anybody can win, and that’s unforgettably exciting. And for those of us who are bystanders, the bracket provides opportunities to argue. Who doesn’t love that?

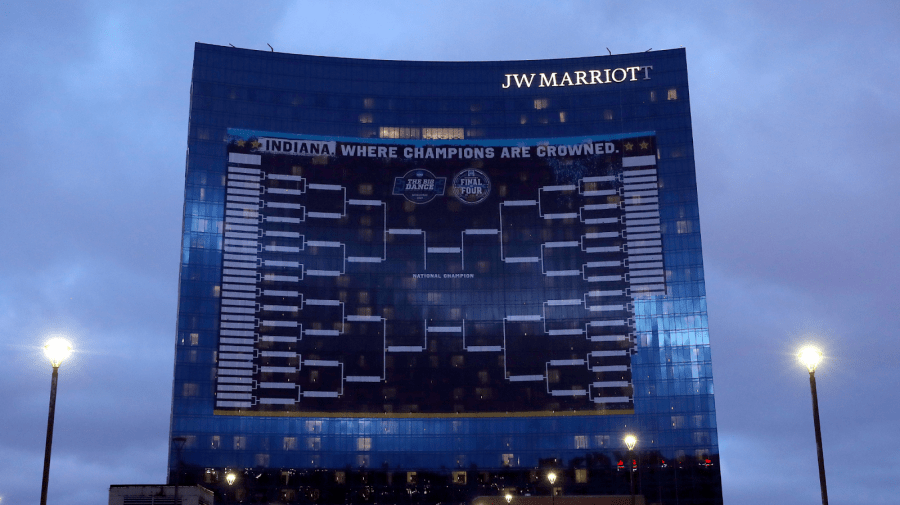

So let’s look at the origins of the tournament bracket, and explore the reasons why it has become — and remained — a cultural phenomenon for all these years.

Starting With a Chess Tournament in London

Basically, the origins of the kinds of single-elimination tournament brackets we see all over the place today stem from 1851. That year, as part of the Great Exhibition in London, Howard Staunton organized a chess tournament. He decided to use a single-elimination format in which players would be matched up in pairs, with the winners facing each other until a final victor was crowned.

A pretty good idea, right? Even so, the concept of the seeded bracket draw didn’t make its way into college hoops until 1939. For it to become the incredibly popular concept it is today, a whole lot of things had to go right. First, there had to be just the right number of teams. As the people in charge started adding teams to the mix, there were years where the bracket itself wasn’t so clean and orderly. The 1959 Men’s NCAA Tournament had 23 teams with nine getting first-round byes. If your eyes glazed over reading that sentence, I can’t really blame you. Eventually, in 1985, the Tournament finally expanded to 64 teams, which ended up being the perfect number.

Next, there had to be enough intrigue to keep things interesting. It’s no coincidence that what ended up becoming “March Madness” really took off in popularity finally in the late 1970s, after UCLA’s run of winning the men’s tournament 10 times between 1964 and 1975 ended. Soon after, the first bracket betting pool took place in 1977 at a bar on Staten Island, and the rest (including my brief foray, years later, into the world of betting pools as a fifth grader) is history.

Madness, Bracketology and Bracketologists

The use of the term “madness” in this context dates back — like the college tournament itself — to 1939, when a former high school hoops coach in Illinois used the phrase to talk about the excitement of fans, who were getting pumped up for the annual state tournament.

But if you ask me, the real evidence that the tournament bracket is an enduring cultural phenomenon is the fact that “bracketology” is an actual word. With increasing coverage of college basketball from organizations like ESPN, the art of talking about the ins and outs of the tournament and predicting its wild swings became omnipresent in inevitable ways.

The crown prince of the bracketologists is Joe Lunardi, who still is providing all your bracketology needs to this day. According to college basketball expert John Gasaway, Lunardi referred to himself as a “bracketologist” in a Philadelphia Inquirer article way back in February of 1996. It makes sense that we’d need such a scientist to help us through the heady days of March Madness.

Brackets Beyond Basketball

You’re probably aware that our collective excitement about brackets has, in the intervening years, spread far beyond the realm of college hoops. Folks absolutely love their brackets. You’ve got classic rock brackets and hip-hop brackets. Last year, Katmai National Park in Alaska did Fat Bear Week, complete with a bracket of the park’s most popular fat bears. There are brackets for the best snack foods and brackets for the worst movie titles.

If you’re wondering how far this kind of thinking could go, here’s one possible answer: back in 2018, Vox did a bracket of pop culture brackets. There you have the entire concept of the bracket basically folding in on itself. Brackets on brackets on brackets.

Why Are We Like This?

In the end, maybe it’s all really simple. Recently, I was at my parents’ house, going through some boxes of old stuff my mom set aside. In one of the boxes, there was a manila folder full of yellowed newspaper pages. I unfolded them, and found a bracket for the 1995 NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament that I had cut out of The Boston Globe when I was a kid. My handwriting, in pencil, showed that I had correctly predicted UCLA as the winner of the tournament (it was their first win since 1975).

Then, the memories really started flooding in: Tyus Edney going the length of the court in 4.8 seconds for a buzzer-beating win in the title game. I remembered how, as a little kid, I snuck off with my older cousin to watch the end of the game at a restaurant bar while my grandmother’s retirement celebration was happening in the next room. I remembered how these brackets, and my conversations around them, have accompanied me through my entire life.

There’s something sweet about it — how we use these brackets to provide some structure to the silly artifacts of pop culture we love to talk about, and about how our arguments and discussions of these artifacts pull us together in surprising and enduring ways. And sure, maybe you could argue that pop culture brackets are designed to annoy you, but maybe that’s actually a little piece of why we love them so much.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman