The Fourth of July may be the most widely known Independence Day in the United States — but it isn’t the only important holiday commemorating independence. Juneteenth, which is also called Emancipation Day, takes place on June 19 every year and memorializes the official end of slavery in the United States.

While this important tradition has been celebrated since 1866, only in recent years has it begun getting more well-deserved attention. Businesses like Twitter, Square and Electronic Arts made Juneteenth an observed company holiday in 2020, and many offer employees a paid day off on June 19, encouraging workers to volunteer in their communities to mark the occasion. On June 17, 2021, President Biden also signed into law a bill that declares Juneteenth an official federal holiday — a decision Bernice King, CEO of The King Center and daughter of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., called “an important moment of reckoning.”

These efforts to recognize the significance of Juneteenth are commendable and foster a much-needed sense of inclusion. But one of the best ways you can begin to appreciate and honor this holiday is to understand the depth of meaning it holds for Black communities. Get started by learning more about the history and importance of Juneteenth, along with the interesting traditions and celebrations that surround it.

What Led to Juneteenth?

On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This document declared that, as of January 1, 1863, any enslaved people in states fighting against the Union in the Civil War were “thenceforward and forever free” and the “Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, [would] recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons.” Although the Emancipation Proclamation was symbolically important and changed the focus of the Civil War from maintaining the Union to ending slavery — and although it appeared to express sweeping freedom for enslaved people — it didn’t actually free anyone.

The Emancipation Proclamation was written to apply to Confederate states that had seceded, but the Union lacked the number of troops it would’ve required to enforce the executive order in Confederate states, particularly in faraway areas like Texas. For this reason, and because communications already traveled slowly in the 1800s, the news of the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t actually make its way to Texas until June of 1865 — two months after the Civil War had officially ended. This difficulty with enforcement, and slaveowners’ resistance to giving up the people who were once classified as their property, is also a primary reason why slavery persisted even after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

Major General Gordon Granger, bearing news of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, arrived with Union troops in Galveston, Texas, on June 18, 1865. Because they were unaware that the Civil War had ended, Confederate troops were still active in the state. The federal government had ordered General Granger to occupy Texas and enforce the Confederates’ surrender. On June 19, General Granger delivered “General Order No. 3,” a military order notifying remaining Confederate troops and the people of Texas that all enslaved people were to be freed immediately.

“Walkin’ on Golden Clouds” — Juneteenth Takes Off

Texas was the last of the Confederate states to have the order read, and upon its announcement, former slaves rejoiced. The language in “General Order No. 3” dictated that the relationship between slave owners and formerly enslaved people would become one of employers and hired laborers, and that enslaved people would no longer be considered property. Upon learning of this, many former slaves left right away — some while General Granger was still reading the order — eager to seek new lives in more welcoming areas of the country.

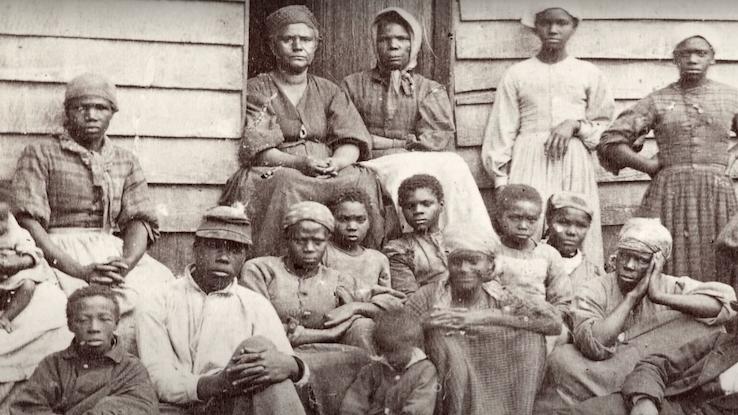

In the wake of this momentous news, many formerly enslaved people immediately “began to celebrate with prayer, feasting, song and dance.” The jubilance was palpable. In providing a statement for a history book about Texas, former slave Felix Haywood described the reactions: “Hallelujah broke out… Everyone was a-singin’. We was all walkin’ on golden clouds… Everybody went wild… We was free. Just like that, we was free.” This revelrous mood and the resulting celebrations were the basis for Manumission Day, which was the original name of Juneteenth.

1866 saw the first official Juneteenth celebrations take place in Texas. Participants gathered in parks to mark the occasion by singing hymns and praying, and they prepared special dishes using meats they were unable to eat while they were enslaved. Participants also dressed up in fine clothes that they weren’t previously permitted to wear. Word of these festivities traveled, and the next year saw Juneteenth events pop up all around Texas.

For the next few decades, Juneteenth celebrations flourished, eventually making their way to other states as freepeople migrated. Despite the former slaves’ newfound freedom, however, they found it increasingly difficult to continue celebrating the new holiday. Laws in many states prevented African Americans from using public property to host these events, and despite finding workarounds such as using church grounds or purchasing properties where people were free to celebrate, interest in commemorating Juneteenth waned in the face of consistent efforts to stifle it. This, coupled with the economic impact of the Great Depression and two world wars, resulted in a decline of Juneteenth events until the middle of the 20th century.

As the Civil Rights Movement began to gain momentum in the 1950s and ’60s, Black activists began calling people’s attention toward historical Juneteenth celebrations. They likened the then-current struggles for justice and equality to the struggles their ancestors had endured, and many leaders and activists specifically called for a revival of commemorating Juneteenth. As participants at marches and protests returned home from these demonstrations, sometimes traveling across the country, they took with them the reminder to reignite their communities’ interest in and desire to celebrate Juneteenth. It worked, and Juneteenth today is recognized on a global scale.

Juneteenth’s Significance and Symbolism

Juneteenth became a state holiday in Texas in 1980, and others followed suit over the past few decades; it’s now set to become a federal holiday in 2021. It’s noteworthy that states — and, now, the federal government — have chosen to honor the holiday this way, and officially designating it as such helps bring awareness to this meaningful occasion. But it’s because Juneteenth is significant that it was designated an official holiday, not the other way around. What does it represent to those who celebrate and to Black communities?

Historian, lawyer and self-professed “soul food scholar” Adrian Miller explains what makes Juneteenth such an important holiday for himself and many others: “It connects me to previous generations of African Americans… I think about all of those Emancipation celebrations, church suppers, family reunions and other occasions when people got together to celebrate, renew family ties and friendships, and affirm their humanity.” The connection to previous generations that Juneteenth fosters helps shape many African Americans’ identities and deepens their sense of self while honoring their ancestors.

Maintaining a sense of community and belonging is another reason why Juneteenth is so significant. When groups gather together and celebrate this holiday, it reinforces the benefits that come from being part of a community — interacting, sharing experiences, fostering a sense of connection. Remembering history in this way supports cross-cultural awareness and understanding, too. And Juneteenth celebrations, like other events, are a great opportunity to socialize, enjoy delicious food and gain some exposure to local artisans and cultural organizations.

Despite the fun and community affirmation, it’s also important to keep in mind that Juneteenth is a powerful reminder for people everywhere. It’s a reminder that freedom and justice for African Americans have always faced delays, that the United States has a long history of oppression that it still needs to acknowledge, confront and dismantle for the benefit of everyone — but especially people of color.

Emancipation Celebrations

Juneteenth traditions are as varied and diverse as the regions of the United States where they’re celebrated. Many of the celebrations reflect local cultures; for example, festivities in the Southwest usually involve rodeos, a longtime cultural institution there, while in the South, people host barbecues and blues concerts and serve strawberry soda, red velvet cake and red fruits.

Why red? The color holds significance for Juneteenth in part because it represents the blood that millions of enslaved people shed for their suffering. But in West Africa, where many people were captured before being forcibly transported to the Americas to endure slavery, red also symbolizes strength. Incorporating that color into the celebrations became a way to honor those ancestors and keep elements of their culture alive.

Red drinks at Juneteenth celebrations have another distinct tie to West Africa, too. Kola nuts and hibiscus, two plants that grow in that area of the continent, have been used for centuries to make teas in Africa, and they both create red liquid when steeped. These plants traveled to the Americas with enslaved Africans, who continued to grow, harvest and prepare them after arriving in the United States. Drinking red teas, sodas and juices at Juneteenth celebrations holds symbolic meaning because it’s a tradition that maintains a tangible connection to previous generations and serves as a reminder to reflect on the hardships they suffered.

Juneteenth celebrations across the country have other common threads, too. Many communities host parades, concerts and cookouts. Public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation often happen at Juneteenth gatherings, and many groups sing traditional spirituals that recount the hardships of slavery. While attending one of these events, it’s common to see Miss Juneteenth pageants and historical reenactments. All of these traditions serve to keep history alive while creating a celebratory, community-focused atmosphere.

Just as meaningful today as it was over 150 years ago, Juneteenth is an event that deserves our respect. It’s a holiday that represents freedom even more so than the Fourth of July does. Although the United States has a lot of work to do in terms of reversing the effects of systemic racism and righting racial inequalities that have persisted for centuries, Juneteenth is a positive representation and celebration of the ways people overcome hardships — and that’s not something we should ever forget.