In 2012, artist Damien Hirst was approached by The Walt Disney Company to produce a piece inspired by the company’s enduring ambassador, Mickey Mouse. The result? A gloss on canvas painting and a subject composed entirely of circles — black, yellow, red and off-white circles, to be exact.

Despite Hirst’s relatively abstract approach to recreating Mickey on canvas, it’s still immediately clear who the artist has painted, even if you see the work removed from any Disney-related context. “It’s using simple means to capture the very essence of his form solely through the power of color,” Hirst said of the painting. “I love that the imagery is so powerful that it only takes twelve different colored dots to create something so instantly recognizable.”

Undoubtedly, this speaks to Mickey Mouse’s timelessness. In 2019, The Walt Disney Family Museum displayed a 2014 version of Hirst’s painting, Mickey for Bob, alongside other depictions of the character as part of a special exhibition-meets-Mickey-retrospective, Mickey Mouse: From Walt to the World. The other featured artists ranged from the likes of pop art authority Andy Warhol to San Francisco-based muralist Sirron Norris; although they varied greatly, the works in this aspect of the exhibition underscored not only Mickey’s continued relevance, but the way in which the character has become much more than a brand ambassador.

On November 18, 2018, Mickey Mouse turned 90, and now, as he nears 100 (and a landmark copyright expiration date), we’re taking a look back on the origins of Walt Disney’s most well-known creation.

Of Mice and Rabbits: The Birth of Mickey Mouse

While Mickey Mouse is a mega-success now — and while Disney owns more characters and properties than we can possibly count — things weren’t always sunshine and rainbows. (Well, maybe not rainbows, because, you know.) In fact, in a 1948 radio broadcast, Walt Disney referred to Mickey as a symbol of his independence.

Just two decades earlier, Walt and his brother Roy Disney owned a modest cartoon studio, if you can believe that. Before the iconic mouse was born, the brothers worked on a variety of other projects, including the Alice Comedies series — which, in a pioneering move, blended live-action and animation — and the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series. The fully animated Oswald shorts weren’t long for this world, however. At the time, (what’s now) Disney simply didn’t have the financial resources to churn out pictures. The Oswald character was Universal Pictures’ star, and Walt was beholden to film producer and distributor Charles Mintz, who unceremoniously took over Margaret J. Winkler’s Winkler Pictures (now Screen Gems) when he married her.

Oswald proved more successful than Mintz could’ve imagined. In February of 1928, Mintz hired away almost all of Disney’s animators and the brothers lost Oswald. “As Walt liked to recall, on a train ride from Manhattan to Hollywood, he brainstormed ideas for a new character,” The Walt Disney Family Museum notes in its Mickey Mouse exhibition catalogue. “After arriving in Los Angeles, he discussed his ideas with animator Ub Iwerks, his longtime friend from Kansas City, and chose a mouse.”

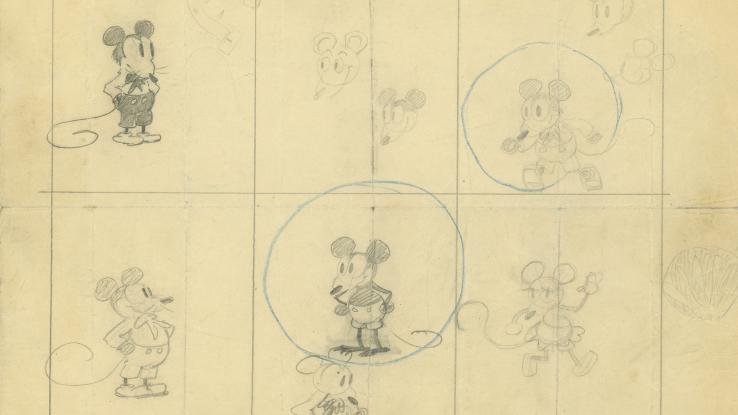

Although it’s not clear who did what when it came to putting pencil to paper, this earliest-known drawing of Mickey (pictured above) is credited to not just Walt, but Iwerks and then-apprentice animator Les Clark. As the story goes, Walt thought about naming the new character Mortimer, but his wife, Lillian Disney, who’d worked as an ink artist at the then-Disney Studios, suggested Mickey instead. “I think we are rather indebted to Charlie Chaplin for the idea,” Walt said in an interview. “We wanted something appealing, and we thought of a tiny bit of a mouse that would have something of the wistfulness of Chaplin — a little fellow trying to do the best he could.”

“Steamboat Willie” Changes the Landscape of Animation

And Mickey’s best? Well, initially, it was something of a far cry from his present-day success. For one, no one had ever heard of Mickey Mouse — or Walt Disney, for that matter — and without a distributor like Mintz the studio had a difficult time getting its shorts into theaters. In fact, the first two Mickey-helmed shorts, Plane Crazy (released later in 1929) and The Gallopin’ Gaucho (released later in 1928), didn’t originally make it into theaters.

At the time, cartoon shorts often ran before feature-length live-action films and were little more than comic-strip panels set to jaunty music. The year before, The Jazz Singer, a live-action picture that featured — amazingly! — sound on film, was a huge hit. And that gave Walt an idea: Why not take the success of the “talkies” and run with it?

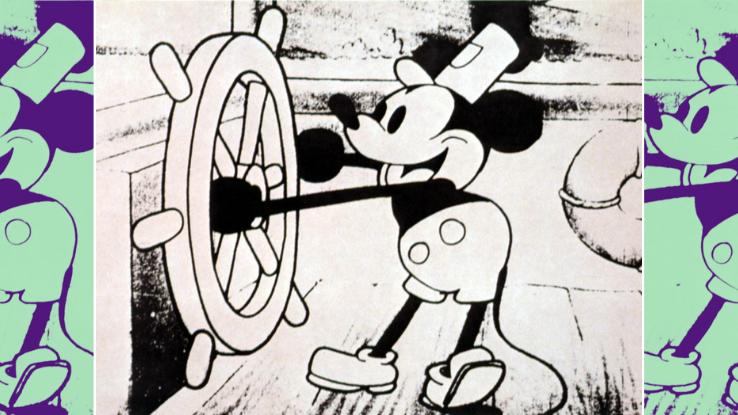

But adding sound to an animated short was quite the challenge back in 1928, especially because Walt wanted the sound to synchronize perfectly with what was happening in the picture. For starters, all of the sound effects had to be recorded in one take. The Mickey short Walt ended up going with for this project was, of course, Steamboat Willie (1928), which runs about eight minutes. So, eight minutes’ worth of sound. All in one take. We sure won’t take TikTok’s editing tools for granted again.

When Steamboat Willie premiered at the Colony Theater in New York City on November 18, 1928, Mickey Mouse’s star power shone through. Voiced by Walt, the character had more personality than animated stars that predated him, like Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur (c. 1914) or Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat (c. 1919). The synchronized sound technique not only captivated audiences, but also theater owners, distributors and filmmakers alike.

Kay Kamen Banks on Mickey’s Commercial Appeal

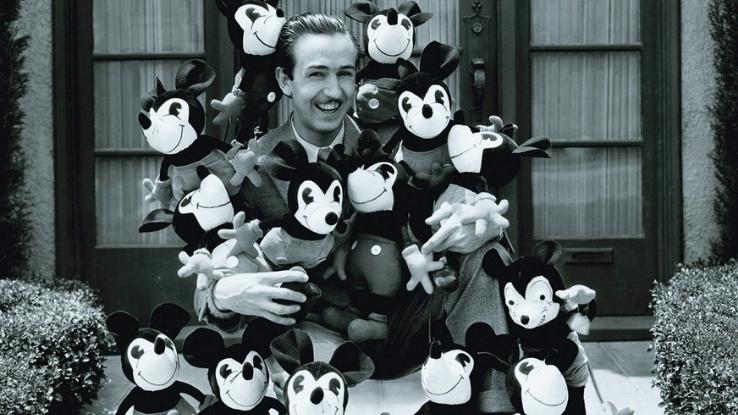

Mickey’s near-overnight success wasn’t contained to the screen, either. Merchandising master Herman “Kay” Kamen struck a deal with Disney and helped Mickey become the most popular character of the 1930s. To license Mickey (and other Disney characters), Kamen withdrew his life savings, sewed the money into his coat (for safekeeping, naturally), and hopped a train to Los Angeles, California.

Monetizing Mickey Mouse’s image provided a much-needed revenue stream for Disney, allowing it to not only stay afloat during the Great Depression, but to produce more Mickey shorts and entries in the Silly Symphonies series, which kicked off with “The Skeleton Dance” in 1929. In The Disneyization of Society, Alan Bryman notes that the revenue from the licensed Disney merchandise totaled over $100 million by 1948.

While Mickey’s image was emblazoned on everything from toothbrushes to lunchboxes and sewing machines, the most popular item wasn’t a Mickey doll or figurine. Arguably, the shiniest item in Kamen’s trophy case was the Mickey Mouse watch. Produced by Connecticut’s Ingersoll-Waterbury Company, the watch, with its illustration of Mickey and moveable arms, became one of the most beloved timepieces in American history.

Although the watches were featured at the Chicago World’s Fair, the real shock came when they hit stores; Macy’s sold a whopping 11,000 Mickey watches on the first day of sales. “Within a year and a half the Ingersoll Waterbury Company had sold over two million watches,” Connecticut History reports, “…[and] added an additional 3,000 employees to their staff.” The clock company that was saved by a mouse is still around today — but you might know it as Timex.

Mickey Mouse Approaches 100 Years of Pop Culture Stardom

During the bulk of the 1930s, Mickey starred in at least 14 short films each year. (Finally, a Hollywood star who might be working harder than Nicolas Cage.) Excluding cameos, Mickey appeared in a staggering 118 films before his hiatus, which began in 1953.

“Walt Disney once said, ‘Mickey was simply a little personality assigned to the purposes of laughter,’ but the mouse — like Walt — transformed the medium of animation and became synonymous with quality entertainment and innovation,” the late Ron Miller, Walt’s son-in-law and former Disney president and CEO, wrote. But while Mickey may have been the face of the company, Disney’s insistence on technical innovation was, perhaps, the real key to enduring success.

After the success of synchronized sound, Disney implemented other groundbreaking techniques and technologies. In 1932, the Silly Symphony called “Flowers and Trees” became the first animated short to employ the full-color three-strip Technicolor process, an innovation that earned the studio its first of many (competitive) Academy Awards.

Other Silly Symphonies and Mickey shorts not only implemented glorious Technicolor, but original songs and music and boundary-pushing technical innovations, including the multiplane camera, which allows filmmakers to create the illusion of depth when filming otherwise flat animation panels. All of this, of course, paved the way for Hollywood’s first full-length animated feature, the Oscar-winning Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), which grossed an impressive $8 million (during the Great Depression, no less).

In addition to opening doors for Disney, Mickey remained a success all his own. In 1932, he earned Walt an honorary Oscar simply for existing, and he even has his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Today, Mickey Mouse and co. are the fourth highest-grossing multimedia franchise of all time — behind Pokémon, Hello Kitty and Winnie the Pooh — with revenue totaling an estimated $80.3 billion. On his own, Mickey’s net worth is estimated to be around $5 billion.

“Even after decades of success,” Miller writes in the foreword to The Walt Disney Family Museum’s exhibition catalogue, “Walt wanted the world to remember that his entertainment empire was ‘all started by a mouse.'”