Editor’s Note: If you’re looking for the latest on the vaccine rollout, vaccine boosters and other developing stories related to vaccination, please visit our Everything We Know About the COVID-19 Vaccine breakdown. To learn more about the changing circumstances regarding COVID-19, be sure to check the CDC website.

In the midst of the United States reporting some of its highest daily case numbers since the pandemic began, pharmaceutical company Pfizer announced that its vaccine candidate was found to be more than 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 infections among people who hadn’t previously contracted the virus. Just weeks later, in mid-November, two more pharmaceutical companies — Moderna and AstraZeneca — reported that Phase 3 testing and preliminary analyses had found their vaccine candidates to be 94.5% and up to 90% effective, respectively. The vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals also received clearance for distribution and was found to be 66.3% effective at preventing the virus during trials.

After applications for Emergency Use Authorization were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December of 2020, vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna have been distributed across the country and administered to most members of the U.S. population. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine’s distribution also resumed following a temporary halt in early April 2021 after the CDC and FDA’s vaccine reporting system found that multiple people had developed a rare blood-clotting disorder upon receiving their dose. While this news was concerning, the overall widespread distribution of vaccines was a huge leap forward for mitigating the spread of the disease — especially considering previous estimates that indicated a vaccine might not be ready until late 2021.

As Symptomfind notes, widely available COVID-19 vaccines are pivotal to protecting our communities and getting us closer to herd immunity. As of August 2021, the FDA has fully approved the Pfizer vaccine – hoping that their endorsement will encourage more people to get vaccinated. So, how were the COVID-19 vaccines developed and how, exactly, do they combat the virus?

How Were the Vaccines Developed?

As you may have heard, the U.S. government enacted an objective called Operation Warp Speed, and despite its sci-fi name, the plan had a very real goal: to develop a vaccine on an accelerated timeline and deliver 300 million doses to the public by January 2021. Vaccinologists later told CNN that this timeline was wildly unrealistic, which proved to be true: By January 6, 2021, just over 17 million doses had been distributed across the country. Fortunately, rollouts began accelerating as vaccine supplies increased in the months afterward.

Initially, in the midst of several unexpected slowdowns in distribution and deployment of the vaccine, we were bombarded with other new treatment possibilities almost daily (some more promising than others). These included the FDA’s aim to use convalescent plasma and the anti-inflammatory corticosteroid dexamethasone, often used to treat conditions like asthma.

Although other governments may not have snappy, Star Trek-sounding monikers for their vaccine-production efforts, it’s clear that scientists around the globe, from those employed by biotech and pharmaceutical companies to those staffing research universities like Oxford, have been working around the clock to develop viable vaccines in record time. According to the University of Michigan’s Michigan Medicine branch, more than 100 potential vaccine candidates were winnowed down to just a handful of promising, trial-ready prospects.

In the July 2020 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, writers outlined the five leading vaccine contenders:

- 1) Moderna (mRNA-1273): A vaccine that uses messenger RNA as a delivery mechanism (more on that later).

- 2) BioNTech and Pfizer: Another messenger RNA-based vaccine. As previously stated, Pfizer has received the FDA’s full approval as of August 2021.

- 3) Merck, Sharpe & Dohme and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative: A vaccine that uses a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vector.

- 4) Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals: A vaccine that utilizes a replication-defective human adenovirus 26 vector.

- 5) AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford: A vaccine that uses a replication-defective simian adenovirus vector.

Breaking Down the Science Behind the Various Vaccines

The Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society — a global organization dedicated to the regulation of healthcare and related products, including pharmaceuticals, biologics and medical devices — has also been tracking the progress of different vaccines. In addition to the contenders and the now-deployed vaccines listed above, the organization is keeping tabs on several others that appear promising. These include a nanoparticle vaccine from biotech company Novavax that’s now in the third phase of the development process, and a live attenuated vaccine formulated out of a joint effort between the University of Melbourne, Radboud University and Massachusetts General Hospital. In total, nearly two dozen vaccine candidates worldwide are now undergoing Phase 3 testing.

The variety of options sounds promising, but these vaccines also come with some potentially confusing lingo. So, let’s quickly break down the differences between some of the leading vaccines:

- What is an adenovirus and why is it being used? To put it simply, adenoviruses are viruses capable of causing the common cold. Michigan Medical School’s associate professor of internal medicine and microbiology and immunology, Adam Lauring, M.D., Ph.D., explains that “For years, people have been using these viruses to deliver DNA, which are instructions for proteins. For the COVID-19 vaccine, researchers swap in a gene from SARS-CoV-2 [the specific strain of coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 illness]. When the vaccine is given to someone, the modified cold virus makes the SARS-CoV2 protein, which stimulates the immune response.”

- Is it better to use a human or a simian adenovirus? While Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals is using a human adenovirus, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford are tapping into a simian (or monkey) adenovirus. Lauring explains that companies aim to “find a virus that not a lot of people have been exposed to before.” If it’s a virus someone has already had, their immune system would likely attack and destroy the vaccine. Needless to say, some companies turn to monkeys for this reason, although neither adenovirus is more effective, per se.

- What is a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus, and why is it being used? To put it simply, it’s a virus that primarily infects livestock, like horses and cows, and, much like the adenoviruses mentioned above, this modified virus delivers instructions for the SARS-CoV-2 protein to our cells. According to Lauring, this method worked wonders for fighting Ebola.

- What are mRNA-based vaccines? Think back to high school biology, and you may recall that DNA is the gene, and RNA provides protein-making instructions. Needless to say, instead of using a virus vector to deliver protein-making instructions, this method simply sends the instructions.

What Is the Timeline for Vaccine Testing and Distribution?

Scientists began working on vaccines in early 2020, almost immediately after the novel coronavirus began making headlines, and various pharmaceutical companies made rapid progress in the immunizations’ development in the ensuing months. Before Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca’s news, results were decidedly mixed: Some vaccine trials helped small animals, like mice, stave off the virus, while other trials saw some symptom mitigation in humans and simian subjects.

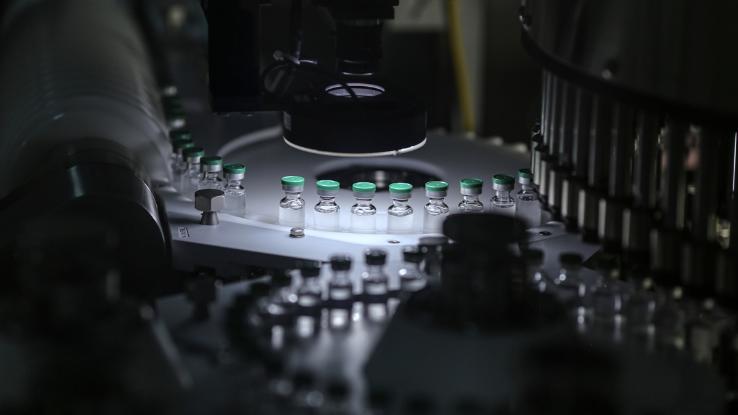

But researchers clearly moved in the right direction. An article on Reference points out that CDC guidelines require that “vaccines pass through six general stages of development: exploratory, pre-clinical, clinical, regulatory review and approval, manufacturing, and quality control. …It’s not unusual for a vaccine to take 10 to 15 years to complete all the phases under normal circumstances.” But considering the accelerated pace at which the recently released COVID-19 vaccines went through development, the United States is now anticipating millions of Americans will be vaccinated by the middle of the year — and for us to potentially reach the level of vaccination required to achieve herd immunity by the end of 2021.

Despite the optimism that the distribution of the vaccines has created, “the effort will hinge on collaboration among a network of companies, federal and state agencies, and on-the-ground health workers in the midst of a pandemic that is spreading faster than ever through the United States,” notes The New York Times. This means there are ample opportunities for hiccups and roadblocks in the vaccine deployment process; each step requires an increased level of cooperation and has variables that can change the outcome on both large and small scales. Ideally, everything will come together within the anticipated time frame and the United States will have enough doses of Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson’s vaccines to treat most American adults by mid-2021. But it may still become necessary to temper expectations somewhat. In the meantime, be sure to read up on our COVID-19 Vaccine Fact Check.